Let’s think back for a minute. Way back. Not just to how people take things for granted nowadays, but to a time when humans first looked around at the world and tried to make sense of it all. You saw a beetle scurry across the ground, a leaf unfurl in the sun, a sibling laugh. You also noticed a stone sitting still, a shadow lengthening, a discarded toy lying inert. What were those first, unspoken recognitions that told you one was alive and the other was not?

Even before formal science, this distinction between the autonomous and the inert was crucial. Knowing what grew could feed you. Understanding animal behavior could keep you safe. Observing the cycles of nature – birth, growth, decay – formed the bedrock of early knowledge. It wasn’t a lab experiment, yet it was a fundamental act of inquiry, a primal form of science unfolding in everyday life.

Consider a simple seed you might plant in a garden. It looks like a tiny, lifeless speck. And yet, with water and warmth, a sprout emerges, reaching for the light. A pebble, under the exact same conditions, remains stubbornly unchanged. Therefore, something inherent within that seed holds a unique power, a capacity for internal action and transformation absent in the stone. You, watching a seed sprout, have echoed this ancient observation, a basic yet profound step in understanding the nature of life.

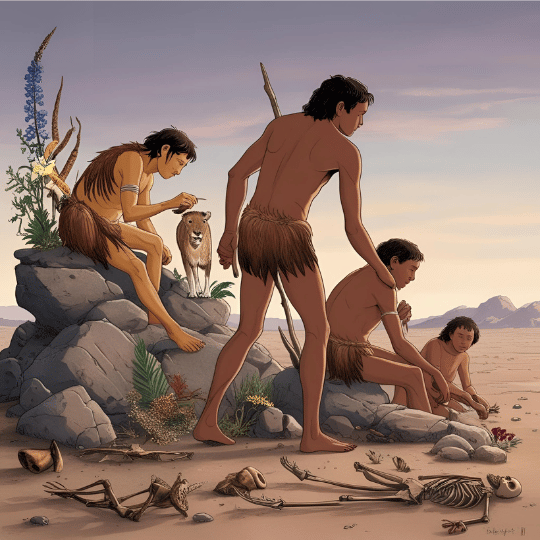

Our ancestors, too, pondered this divide. They saw flames dance and rivers flow. And they also watched creatures move with apparent intention, reproduce their kind, and eventually cease to function. Perhaps they imagined spirits within the moving water or the rustling leaves. However, as human thought matured, a more systematic approach began to emerge. Think of early attempts to sort and categorize – the strong animals versus the swift, the plants that heal versus those that harm. This wasn’t a textbook exercise, but it was a vital step in organizing observations, much like sorting your collection of rocks or shells.

You might be thinking, “Well, of course, living things move and grow!” And you’re right; these are key initial recognitions. Still, the path to understanding life’s intricacies has been paved with careful attention to even these seemingly obvious differences. By systematically noting these characteristics, by drawing general ideas from specific instances (like noticing that all the birds they observed laid eggs), and by building logical connections between these observations, early thinkers started to build a framework for understanding the living world.

The earliest thinkers to systematically identify properties distinguishing living beings from non-living objects were Greek philosophers, particularly Aristotle (384-322 BC) and his student Theophrastus (370-285 BC). Aristotle, for example, based his classifications of organisms on their attributes, such as movement, growth, and respiration, which he used to separate plants and animals (see his History of Animals). Theophrastus continued this tradition, focusing on plant classifications and uses in his Historia Plantarum.

Think about a breath of air. You take it without conscious effort most of the time, but what you exhale is different from what went inside your lungs. And yet, this exchange with the environment is a defining feature of being alive. A rock doesn’t breathe. Wind pushes a cloud across the sky, but it doesn’t inhale or exhale. This simple act points to an internal process sustaining life, a continuous interaction with the surroundings. Consequently, even in this basic function, we see a fundamental split between the animate and the inanimate. Your own experience of needing to breathe underscores this essential distinction.

But what makes living beings alive is not only how they function and respond to the environment, there is something deeper going on at a level where the unaided eye cannot easily access, if it wasn’t for tools like the microscope which allow us to penetrate down to a molecular level.

So, as we begin our journey into the fascinating history of how we came to understand DNA and epigenetics, remember this initial, crucial step: distinguishing the living from the non-living. It began with direct, intuitive observations, much like your own explorations of the world. And through methodical observation, reasoned thought, and the accumulation of knowledge across countless generations, we have progressed from these fundamental distinctions to the breathtaking complexity of the molecular realm. This ongoing quest, much like a detective piecing together clues, highlights the power of human curiosity and our inherent drive to unravel the mysteries of existence. We start with what seems elementary, yet it forms the bedrock upon which our most advanced scientific understanding is constructed.

If you would like to delve deeper into, what scientists call, the code of life, you can access our full curriculum on DNA by ordering our DNA Model Kit and start your hands-on learning/teaching journey with DNA & Beyond!